After emancipation, some southern planters whose former enslaved left the property never to return had little choice but to lease land to freedmen in return for a portion of their crops under a sharecropping system. Others southern planters whose former enslaved remained on the property in the very cabins they had lived under a tenant farming system whereby tenants worked an allotted time on the plantation in exchange for “rental property” on which to grow their own crops. Sharecropping and land tenancy, however, made it difficult for newly freedmen to advance their position in society. Agricultural depression also led many white farmers to become sharecroppers and tenants when forced to sell their land and look for work like black farmers. By 1880, tenant farms made up one-third of North Carolina’s agricultural operations.

While tenancy and sharecropping shared similarities, there were also differences between them. Both systems allowed laborers to work a plot of land and divide their harvest with the landowner according to the negotiated contract. The systems offered the illusion of independence to black laborers. Farm tenants alone, however, owned their crops outright, possessed the authority to plant the crops of their own choosing and in the manner they pleased. Though crop liens weakened this authority, tenants nevertheless enjoyed greater autonomy than sharecroppers. The tenancy system would eventually place both black and white farmers into a cycle of debt. Unable to acquire sufficient capital to purchase their own land, laborers were caught in restrictive contracts that prevented their mobility or ability to negotiate better terms.

At Poplar Grove, the majority of the Foy’s enslaved remained on the plantation after emancipation. Having chosen surnames to reflect their new-found freedom, family bonds solidified and African American men began the process of securing their own households. Here, the rent for housing and subsistence land was free. The tenant families primarily inhabited the cabins of their enslavement on the property, as well as a few new buildings, simply constructed of unfinished lumber during the late nineteenth century.

The tenant farmers roles did not differ from those of their enslaved days for both men and women. Trusted “hands” responsible for carrying produce to downtown Market Street by mule and cart still did so; however, the opportunity to travel was a new condition of freedom and afforded to all those tenant farmers willing to lose a night’s sleep to make the trip. From the old Market House, the tenant farmers could sell their own produce grown from the small garden plot each had been allotted, or carry their employer-in-name-only produce to market.

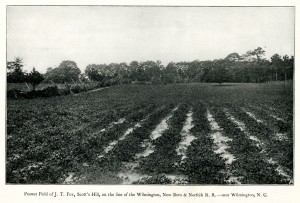

In reference to a request for data regarding J.T. Foy’s farm work, he writes: My first strawberries were planted in 1892. I was inexperienced, and only planted one-half acre; my net returns, after deducting all expenses, were $125.00. I used only home fertilizers.

In sweet potatoes, I have raised 404 bushels of marketable potatoes per acre, after having first gathered a large crop of yellow rutabaga turnips from same land; price ranging from 40 cents to $1.00 per bushel for potatoes. Turnips were fed to cattle and not marketed. Used no commercial fertilizer, but large quantity of barn-yard manure. Began marketing sweet potatoes this season on August 5th, and got $1.50 per bushel. Have made on 40-acre field of peanuts an average of 50 bushels to the acre, price ranging from 50 cents to $1.00 per bushel.

Melons grow very easily with us and are prolific producers. I estimate my melon crop as worth about $50.00 per acre net.

Oats do well, and we can make very fair yield.

I commence cutting asparagus about 1st of March, and shipments last six weeks to two months; can make good crops and find ready sale for same. I only plant corn for home use, and raise all my own pork. I market spring lambs by Easter Sunday, and get $2.00 to $2.50 per head; at no expense for feeding, simply let them run at large” (Scott’s Hill, N.C., August 6, 1896).

J.T. Foy’s use of the pronoun “I” when referring to the labor of his tenants, like most southern planters of his era, is indicative of co-opting the effort and skills of his tenant farmers as his own. The Foy farm hired monthly “hands” who worked annual contracts, with a tenancy of one or two years. Some stayed for the duration of their lives and others enjoyed the mobility of moving from job to job annually. If extra hands were needed, sometimes thirty-five to forty additional laborers, “you get the first choice of people from your family to work.” they were paid daily. Women received thirty-five cents per day and men received forty cents. Leslie Foy remembers a man who didn’t live on the property, and owned his home, was paid seventy-five cents a day for being an excellent plowman. However, farm hands were paid ten dollars per month and were provided with rations, a house, and a garden plot.

Each Friday night, according to Leslie Foy, son of Francis Marion Foy, the tenant farmer drew a ration “of four pounds of meat, a peck of cornmeal, four pounds of lard, a quart of molasses, and some other things,” such as further provisions from the farm store, as the families were not provided flour as part of their rations nor shoes. Shoes could be purchased for ninety-five cents. Each family had a garden plot for vegetables, and they raised their own chickens, which supplied eggs and additional herbs. Some also added to their livelihood through hunting and fishing along the waterways. An account was kept for each person’s wages, and this could be drawn against throughout the year. One man, having earned $120.00 in a year, according to Leslie Foy, had $60.00 left at Christmas.

Robert Lee Foy, Jr., the last Foy family member to own Poplar Grove, recollected the lives of the tenant farmers he worked with at Scotts Hill: “They lived a simple life just like every one else. They lived on seafood, cured pork, corn bread, biscuits, black eyed peas, dried butter beans. That was the staple. They also ate a lot of molasses.” On the delicacy of molasses and homemade biscuits, he noted, “Oh, yeah. That’s good eating. Take hot biscuits, molasses and butter. That’s good eating with a glass of milk. And hoppin’ john is black eyed peas and rice. The molasses is black strap. A lot of [cane] syrup in this area is for home use.”

Nora Foy Brown, daughter of David Foy, an African American tenant farmer at Scotts Hill, and her mother, Emma Harper Foy, who cooked in the Foy household, remembered her father “worked in the field, chopped peanuts.” At harvest time, there was also “watermelon time, cantaloupe time, butter bean time, cucumber time, digging sweet potatoes, and picking up peanuts … they had an old Uncle, named Mr. Smith, he had a peanut house and he’d stack his peanuts in the house in the winter time, and we’d go down there and pick peanuts for 10 cent a bushel, and put blankets over them, we used to keep them from getting cold.” See full interview: Oral Interview Mrs Nora Foy Brown.

David Foy, along with other tenants like Israel Jackson, would load up watermelons and cantaloupes in a mule and cart to take to market in Wilmington. Israel carried a load of Mr. Foy’s produce, while Nora’s father “used to carry his on a mule and cart, get up at twelve o’clock at night, and load that wagon, and we’d go to town, and daybreak we’d be in Wilmington.” The mule cart would travel to the foot of Market Street, then her father would, “Back that mule up side and sell things right on the street.”

Harvest time also signaled one of Nora Foy Brown’s memories as a little girl, which was picking up and eating sparkleberries. “Sparkleberry was like a little tree, something like a hedge, and it had black berries on it, and it come in the fall of the year like Chinquapin.” With the Chinquapin nuts, which she said were about as big as a hickory nut, they “would get a big needle and put a hole in it and string them like beads and wear them around our neck.”

“We used to go down there (Poplar Grove) every day when grandmamma (Mary Jane Harper) was working down there. We used to go down there and do things for her, she was frosting potatoes, you know. When they’d eat the dinner, and you know, her people wouldn’t eat it all, and she would give it to us, wrap it up in a pail, and we’d go back home, go back home with it, some days she wouldn’t give us nothing, and we’d be crying.”

Emma Harper, right; Mary Jane Hines, left. “Laundry Hanging & Hog Killing Time,” Smoke House at Poplar Grove, 1934

Robert Lee Foy, Jr. remembers “the wash water was caught in the cistern. The gutters on the house ran into that cistern. There were one or two rain barrels. When it rained, they would take off the wooden lids and let the water go in and when they got full they put the lids back on. This was to keep the mosquitoes out. This water was used to wash the clothes, hair. They had big wash pots. They would put the clothes and water in the big pots and boil them right in the back yard between the windmill and the garage. There were three wash pots set up. They would boil the clothes and stir them with a big wooden stick, and there was big tin tub with a wash board, and they used lye soap then. There was another tub they rinsed in.” “They” refers most likely to Mary Jane Harper and her daughter, Emma Harper Foy. “She kept us in line. If she saw us doing something we should not be doing, she would stop us.”

Because Poplar Grove was directly across the street from the railroad station, Nora remembers “When we heard the train coming, we’d get down and put our ears to the track, and we’d say, ‘The train coming now,’ and we’d jump and run. And when the train passing, we would go back and put our head down, and say, ‘The train out of sight now.'”

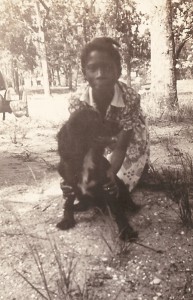

Another endeared and hard-working African-American female, Cornelia Durham, was also employed by Robert Lee Foy. His youngest daughter, Mary Frances Foy Sanders, remembers walking to the top of the hill by the current Scotts Hill Baptist Church where Cornelia Durham lived to retreat into the safety of her warm bed. Above is a photograph taken by Mary Frances of Cornelia’s daughter, Florence Durham.

While visiting Poplar Grove today, one can view inside the last surviving tenant house (c. 1880s), only one remaining of eleven single and double-sided cabins on the open lawns of the backside of the Manor House. Displayed are the simple furnishings and close quarters that were kept by the tenant farmers who lived and worked at Poplar Grove.

References & Further Reading

Alexander, Roberta Sue. North Carolina Faces the Freedmen: Race Relations During Presidential Reconstruction, 1865-67. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1985.

Billings, Dwight B. Planters and the Making of A “New South”: Class, Politics, and Development in North Carolina, 1865-1900. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979.

Daniel, Pete. Dispossession: Discrimination Against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Fite, Gilbert C. Cotton Fields No More: Southern Agriculture 1865-1980. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1984.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 1988.

Foy, Leslie. Oral Interview, January 30, 1980.

Links & Further Information

North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services.