“Sitting by the roadside on a summer’s day

Chatting with my mess-mates, passing time away

Lying in the shadows underneath the trees

Goodness, how delicious, eating goober peas.

Peas, peas, peas, peas

Eating goober peas

Goodness, how delicious,

Eating goober peas”

from “Goober Peas,” a Civil War Era song published in 1866 by A. E. Blackmar

Peanuts are most often associated with the Portuguese. In the early 1500s, the Portuguese established ports in Brazil, African and the East Indies, introducing the Old World to the New World, and thus “the peanut came to be produced in extensive coastal regions of Africa” (Johnson 24). When Christopher Columbus initiated the biological revolution known as the “Columbian Exchange” with his three voyages to the New World, the peanut would soon be carried around the world; however, the peanut, or legume, was not unfamiliar to the ancient and medieval worlds of West Africa.

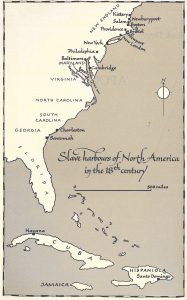

Map Courtesy of The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440-1870 by Hugh Thomas, 1997

The peanut is first noted in the writings of Bartolomé de las Casas, who came to the Caribbean island of Hispaniola in 1502. Called mani by Native Americans, the peanut was considered a healthy food by the Caribbean islanders, but the Spanish considered it beneath their station to make it part of their own diet. Spanish galleons began carrying the peanut to the Pacific Islands, the Philippines, and Indonesia by the early seventeenth century, where it became a part of the Asian cuisine. Portuguese sailors, who claimed Brazil in 1500, had already begun taking additional peanut varieties to the coast of West Africa.

Little evidence exists to prove that the peanut was cultivated in the area that is now the United States before European colonization. Yet “as early as 1687, a young physician, Sir Hans Sloane, living in the West Indies, found many of these crops growing on the island of Jamaica. These plants reached the mainland of North America either directly from Africa, or came with enslaved Africans destined for North America and through trade with the West Indies. These crops may have already found a home in North America before Sloane’s encounter. Eventually, however, these crops went from being eaten exclusively by Africans in North America to being in white southern cuisine” (Holloway, Joseph).

North Carolina seems to be the epicenter of peanut cultivation in the 18th century. One of the earliest records suggests that in 1769, a Dr. Brownrigg experimented in extracting oil from peanuts in Edenton, North Carolina. His findings were later converted into a paper for the Royal Society of London. Commercially-grown peanuts, or ground peas, first appeared in the Lower Cape Fear region of North Carolina around 1818. Their popularity as a staple to feed the enslaved, as well as fodder for hogs, increased their production. The status of the peanut is best reflected in its lack of advertising in the Wilmington trades during the first half of the 19th century. As noted in The Peanut Story, “for more than a quarter century before the Civil War the port of Wilmington, NC, was exporting in the coastal trade thousands of bushels of peanuts yearly, but no merchant of the city seems to have advertised them while notices on imported nuts appear frequently” (Johnson 43).

Peanuts would mainly be used to provision the enslaved while enduring the transatlantic slave trade’s infamous Middle Passage from West Africa to the New World. The term goober as used in the United States is manifestly derived from goba or guba by which the groundnut is known all over the continent except in the Congo where it is pronounced nguba” (Johnson 28). Cultural historians of American foodways are still unsure of how the enslaved actually prepared peanuts for consumption. Most note that peanuts were usually eaten raw, roasted, or boiled. In the South, African American cooks introduced the peanut into local consumption.

Much like sweet potatoes, the peanut’s cultivation was introduced to the plantation master by his enslaved, who often “lay the unshelled peanuts upon a hot hearth, covered them with ashes, banked with live coals and baked in the delightful flavor … eventually it found its way to the large garden that supplied the planter’s household and guests. It also spread from the plantation to the small slave-holders, slave-less whites and free Negroes” (Johnson 38). “Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro” asserted that “The South Carolina Sea Islands people believed peanut seed should be planted on the full of the moon or the pods would not fill up” (Johnson 64). By the 1830s, Wilmington newspapers advertised the latest prices and before the Civil War, the enslaved were known to have hauled carts of ground peas to the foot of Market Street for sale.

The Carolina Housewife, first published in 1847, by Sarah Rutledge of Charleston, South Carolina, references several recipes passed down from the enslaved Gullah cooks, that were most popular in the kitchens of plantations up and down the Gullah Geechee Corridor, including a form of almond brittle, or “Ekabalaroolas.” Peanuts made an excellent substitute for almonds. Simply blanch and fry the raw peanuts in “a small tablespoon of fresh butter, until light brown; then wipe them into a bowl or pan. Make a syrup with a pound or loaf sugar and three gills of water; boil it to a thread (care must be taken to boil it to exact candying point); pour it boiling upon the almonds or peanuts, and stir them until the sugar hardens around them. A perfect peanut brittle. The peanut substitute was called ‘Hindoo Receipt.'”

Joseph Mumford Foy produced about 2,500 bushels of ground peas in 1850, and doubled his crop output by the end of the decade with 5,000 bushels harvested in 1860. Foy’s neighbor, Nicholas Nixon of Porters Neck Plantation, revolutionized the cultivation of peanuts in the 1850s. Nixon’s interest in scientific farming and crop rotation led him to apply one of the earliest known versions of mechanized harvesting with the invention of a steam-powered thresher in 1856. Nixon brought in about $6,000 annually from his peanut crop. Both Nixon and Foy contributed regularly to publications like the Carolina Farmer and Country Gentleman on the issues of scientific agriculture.

Peanuts also provided nourishment to fatten up hogs which foraged the Scotts Hill farms. The Foys were then provided with an excellent source of meat and an additional generator of capital through the sale of pork. In 1860, Poplar Grove had three hundred hogs on site, and had slaughtered $960 worth of meat in the previous year. Soon after the outbreak of the Civil War, Mary Ann Simmons Foy would pledge to aid the Confederate Army with pork if her 2nd son, Joseph Thompson Foy (J. T.), were exempted from service.

By 1860, eastern North Carolina farmers found peanuts to be more profitable than cotton. The United States annual production reached 150,000 bushels, with two-thirds of the national crop being produced in North Carolina. Joseph M. Foy was regularly shipping peanuts to Philadelphia and New York before the Civil War. Union troops even confiscated fifty bushels of ground peas from the Foy’s when they passed through in 1865. After his father’s death, J. T. Foy continued the cultivation of peanuts with the African American tenant farmers working at Scotts Hill, sending peanuts to New York by way of Alexander Sprunt and Sons agricultural shipping business in Wilmington.

The production of peanuts before and after the Civil War when compared to other exports, especially as it relates to the decimation of the naval stores exports, demonstrate an increase rather than a decrease in production.

COMPARATIVE STATEMENT OF EXPORTS

Both Coastwise and Foreign, from the port of Wilmington, N. C., for the years ending December 31st, 1860, and December 31st, 1870,

as compiled from the columns of the DAILY JOURNAL

| ARTICLES | COASTWISE | ….. | FOREIGN | ….. |

| 1860 | 1870 | 1860 | 1870 | |

| Spirits Turpentine, bbls | 127,562 | 68,966 | 20,400 | 32,889 |

| Crude Turpentine, bbls | 52,175 | 12,929 | 23,548 | 3,258 |

| Rosin, bbls | 440,132 | 483,546 | 57,425 | 26,127 |

| Tar, bbls | 43 056 | 54,090 | 6,120 | 6,107 |

| Pitch, bbls | 5,489 | 4,624 | 784 | 190 |

| Cotton, bales | 22,851 | 51,617 | ….. | 20 |

| Cotton Yarn, bales | 1,561 | 72 | ….. | ….. |

| Cotton Sheeting, bales | 1,750 | 547 | ….. | ….. |

| Pea Nuts, bushels | 99,743 | 124,296 | ….. | ….. |

| Lumber, P. P., feat | 9,126,176 | 11,515,123 | 9,882,078 | 8,378,861 |

| Timber, P. P., feet | 22,600 | 290,789 | 20,000 | 85,400 |

| Shingles | 730,880 | 4,804,890 | 2,887,870 | 2,339,334 |

| Staves, Cypress | ….. | 482,253 | ….. | ….. |

| Staves, Oak | 94,723 | ….. | 10,000 | ….. |

Table from https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/haddock/haddock.html

The U.S. Weather Bureau, Wilmington, N.C., notes at the turn of the 20th century, that “the pine-trees of eastern North Carolina no longer yields the great quantities of turpentine that it once did, and new industries are springing up in that land, where once the tar-kiln burned and the turpentine hand went from tree to tree ‘tending his crops of boxes.’ The average temperature for the year for the city of Wilmington, from twenty-five years’ observations, is 63, the warmest year being 65 in 1890, and the coolest 61 in 1888. The warmest month of the year, July, has a normal temperature of 80, the highest mean being 84 in 1875, and the lowest mean 77 in 1890. The heaviest seasonal rainfall occurring during the summer months, averaging 20.62 inches, in connection with the time of greatest heat, produces a luxuriant growth of vegetation, and affords abundant moisture to crops during the period most needed.”

A local neighbor remembers long conversations with Robert Lee Foy, Sr., and in an interview from 1979, recalls that “Mr. Foy had a lot to do with starting the peanut business around here. Mr. Foy went in with Mr. Joe Howard of Hampstead and built a big peanut plant at Hampstead. They shipped peanuts all over the world from there. He had cows and hogs. He raised hogs, so after they harvested the peanuts, he would put the hogs in the fields to clean up what peanuts were left. They would fatten real fast on the peanuts, and he would sell the hogs.

Mr. Foy (Sr.) showed me where there was a peanut plant. Back then when they had that peanut plant they didn’t have combines and thrashers. The peanut plant was run by steam engine and boiler.

In the 1930s, Robert Lee Foy, Sr. had the only peanut thrasher in the area, and all the farmers came to Poplar Grove to use the thrasher. “Farmers from miles around would haul their peanuts in by mules and carts to have them thrashed. This was on the plantation. It was located back of where Mr. Foy’s barn is now. Back of that woods. Mr. Foy also had a peanut plant where they cleaned and shelled them, graded and bagged the peanuts. It was in the old building in front of the old barn. They called that the peanut shack.”

Jerry, the daughter of Robert Lee Foy, Sr., recalls enjoying “molasses candy with peanuts and peanut brittle, also taffy candy. Peanut and corn shelling parties were held to shell them for planting. Prizes were given for the first one to finish his supply. These were fun parties as well as being helpful.”

The Star News of July 5, 1983, interviewed Carrie Simmons Ballard, who was born at Poplar Grove on April 4, 1905: “As a child, she ‘put in many hours picking peanuts on The Big Lot’ where her great-grandmother was the main house servant for the Foy family. Her grandmother and mother also worked for the family. ‘They grew some cotton too, but the main farm product was peanuts,’ she said. ‘I never did much cotton picking, but I sure did my share in the peanut fields.’

“Her older brother ‘manned the gate outside the plantation the third Sunday of every August, when folks would come from miles around for a camp meeting, a revival held in bush tents a few miles from the plantation. ‘People coming from Wilmington had to pass through that gate to get to the meeting, and my brother would stand there and open and close the gate for cars,’ she said. ‘People would give him a nickel and he thought he had some money.’

“‘The thing that stands out most in my mind was how hard we worked for so little,’ she said. ‘It seemed like we had to works so hard for just some food and barely something to wear. But it helped make me the woman I am today – I’m not afraid of working'” (Morgan 1C).

On view in the Agricultural Building at Poplar Grove is an authentic peanut thrasher and other implements used for planting and harvesting peanuts.

On view in the Agricultural Building at Poplar Grove is an authentic peanut thrasher and other implements used for planting and harvesting peanuts.

For Further Reading

Johnson, Roy F. The Peanut Story. Murfreesboro, NC: Johnson Publishing Co., 1964.

Morgan, Patty. I Sure Did My Share in the Peanut Fields. Wilmington Morning Star, Tuesday, July 5, 1983, 1C.

National Peanut Board <http://nationalpeanutboard.org/peanut-info/how-peanuts-grow.htm>.

Smith, Andrew F. Peanuts: The Illustrious History of the Goober Pea. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

The Peanut Institute <http://www.peanut-institute.org/peanut-facts/>.

Virginia Carolinas Peanut <http://aboutpeanuts.com/peanut-facts/origin-and-history-of-peanuts/>.