Like plantations all over the southeastern coastal region, “enslaved Africans had many talents that helped keep the village- like plantation running smoothly and required little or no added expense to the owners. Planters relied on slaves to provide their services as blacksmiths, carpenters, shoemakers, spinners, tanners, coopers, weavers, and other artisan skills” (NPS 38).

Like plantations all over the southeastern coastal region, “enslaved Africans had many talents that helped keep the village- like plantation running smoothly and required little or no added expense to the owners. Planters relied on slaves to provide their services as blacksmiths, carpenters, shoemakers, spinners, tanners, coopers, weavers, and other artisan skills” (NPS 38).

The Age of Iron in West Africa from the Metropolitan Museum of Art states that “In the period from 1400 to 1600, iron technology appears to have been one of a series of fundamental social assets that facilitated the growth of significant centralized kingdoms in the western Sudan and along the Guinea coast of West Africa. The fabrication of iron tools and weapons allowed for the kind of extensive systematized agriculture, efficient hunting, and successful warfare necessary to sustain large urban centers” (www.metmuseum.org).

There were many specializations within the blacksmithing trade. In addition to the blacksmith, Dallas Bogen notes other similar metal-working trades that included “the white smith, tin smith, copper smith, locksmith, silversmith, gun smith, gold smith, saw smith, wheel wright, ship smiths, and many others. The white smith takes the work of the blacksmith and files and finishes it until the base metal shines brightly” (Bogen). There were were also anvil and heavy-tool makers, spoonsmiths, cutlers, farriers, nailers, and carriage-smiths.

From The Tools and Trade Techniques of the Blacksmith, “The tools of the blacksmith varied from time to time and from place to place. They were generally divided into three groups. The first is the hearth with its bellows, water trough, shovels, tongs, rake, poker, and a water container for damping down the fire and cooling objects. The second group consists of the anvil, sledges, tongs, swages, cutters, chisels, and hammers. The third group was made up of the shoeing box, which contains knives, rasps, and files for preparing the horse’s hooves for shoes, an iron stand for supporting the horse’s foot while working on it, and a special hammer and nails to fasten the shoe to the hoof” (Kaufman).

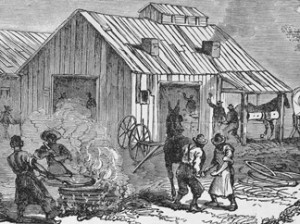

The blacksmith that most people think of is the village smith. He shoed horses, repaired wagons and carriages … in fact he repaired all broken iron and steel items. His shop was the source of hardware that was made to fit specific applications, or what was not available from a local merchant.

His shop was a busy place. Men talked and gossiped while waiting for their work to be done. Children hung around the smithy (blacksmith) and watched the smith and his apprentice forge the hot iron into its final shape. The smith and his helper worked steadily, moving from forge to anvil and back again to heat the iron and shape it. The clicking of the bellows and the gentle roar of the forge fire alternating with the ring of hammers and hot iron on the anvil was hypnotizing.

Sometimes, there was bench work to be done, and the screech of a file on cold steel would grate on the ears. Horses waiting to be shod would stamp and whinny.

The blacksmith on an antebellum plantation was most valued, spending most of his day as any colonial village blacksmith, repairing worn tools and equipment – tasks generally assigned to skilled adult male slaves.

At different times of the year, plows, corn knives, and harrows needed sharpening. All year the draught animals had to kept trimmed and healthy. Years ago most people took their horses and mules to the smith if they were sick or lame. Most farm and plantation smiths were veterinarians, and lame or sick horses and mules were tended by the blacksmith.

By the middle of the 19th century most metal goods were purchased in hardware stores or through catalogues. However, traditional smiths continued to make axes, door latches, hinges, locks, and many blacksmith and wagon-wright tools, which left blacksmiths doing a lot of repair work.

At Poplar Grove, a local neighbor recalls that Robert Lee Foy, Sr., “had a lot of those two wheel carts with real high wheels he used because they were easier to use in the sand than those four wheel carts. The blacksmiths built those carts.” His son, Robert Lee Foy, Jr., remembers that on the farm “there was a blacksmith shop, and they forged a lot of their tools. They [tenant farmers] made plows, axes, and the tools that went on the plows. You would be surprised what they could heat and bend and make into tools.

They[tenant farmers] made and repaired the spokes and wheels for the wagons. They put the metal rim that went on the outside of the wooden wheel. they built a fire all the way around it and heated it and expanded it, then slipped it over there, then poured water on it right quick and it shrank right over it. That is how a rim was put on a wheel. One of the old blacksmith forges is still down there. You put the coal in there, and it had a handle you pumped, and it heated up, and you could put a horseshoe in there and shape it to fit that horse’s foot. They welded with heat” (Interview, 1979).

This page is currently under construction.

Sources

National Park Service (NPS). Low Country Gullah Culture Special Resource Study and Final Environmental Impact Statement. Atlanta, GA: NPS Southeast Regional Office, 2005.