The Historic House & Museum Are Currently Closed for the Winter Season.

See You All February 2026!

PUBLIC STATEMENT

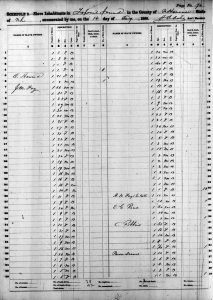

left Melvina Dozier Foy; seated Nora Dozier Foy; Leslie Foy; Cleveland Nixon holding George Nixon

The history of Scotts Hill, Pender County, North Carolina is reflected in this historic site. History is always moving, and continues to shape how we move forward as an historic site.

Black history is American history. The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission (GGCHCC), of which Poplar Grove is a part, recognizes that “Historic sites carry potent literal and symbolic messages across generations. We (GGCHCC) encourage you to visit them and ask yourself important questions about the history they share and the stories that are left out.”

What stories will Poplar Grove carry forward? Part of Poplar Grove’s mission is to initiate meaningful dialogue that builds upon the values of respect, empathy, cultural diversity, multiple perspectives, and democratic principles, especially as it relates to the history of the northeast branch of the Cape Fear River and Topsail Sound in the production of naval stores, indigo, peanuts, sweet potatoes, and melons.

We will be expanding our exhibits and tour text to include Poplar Grove’s Revolutionary War history through the lens of a collective and shared experience – locally, nationally, globally, spiritually.

Poplar Grove Foundation, Inc., January 1, 2024

Located in southeastern North Carolina and within the National Park Service’s Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, Poplar Grove historic house and museum, formerly a sweet potato and peanut  plantation, produced peanuts from the agricultural skills of the Gullah Geechee people. The sweet potatoes and peanuts were sold locally to planter families to supplement the diet of the enslaved community. The highly protein-packed food source crossed racial lines during the Civil War to feed both Union and Confederate troops, and in the last decade of the 19th century, Wilmington peanuts were shipped as far north as New York City before P.T. Barnum’s traveling circus would popularize this Gullah crop to the masses.

plantation, produced peanuts from the agricultural skills of the Gullah Geechee people. The sweet potatoes and peanuts were sold locally to planter families to supplement the diet of the enslaved community. The highly protein-packed food source crossed racial lines during the Civil War to feed both Union and Confederate troops, and in the last decade of the 19th century, Wilmington peanuts were shipped as far north as New York City before P.T. Barnum’s traveling circus would popularize this Gullah crop to the masses.

The museum complex is sustained through the continuing efforts of Poplar Grove Foundation, Inc., a 501(c)(3) non-profit Public Charity, dedicated to education, conservation, and preservation. The current manor house was restored and opened to the public as a museum in 1980 and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The 15+ remaining acres left of the original homestead are under the stewardship of the North Carolina Coastal Land Trust.

Poplar Grove Foundation, Inc. seeks to shed light on this pre-Revolutionary War planter family who originally settled in New Bern, NC, from Baltimore, Maryland circa 1760. Foy family members and those people this family enslaved played an integral part in eastern North Carolina’s agricultural development and actively participated in North Carolina’s Revolutionary War. The land, and its original manor house, mill pond, brick kiln, and out buildings, was purchased in 1795 by James Foy, Jr. of New Bern, NC, from the estate of Cornelius Harnett, a leading Revolutionary North Carolinian politician.

After the original homestead burned circa 1849, Joseph Mumford Foy, the grandson of James Foy, Jr., chose to construct his new home closer to the Old New Bern Road, which would later become the Wilmington and Topsail Sound Plank Road. The current manor house was built circa 1850, constructed and maintained by the skills of enslaved men and women within the Foy family as well as from enslaved male artisans of neighboring planter families, such as Nicholas Nixon of Porters Neck, David Ward Simmons of New Bern, NC, and the Doziers of Brittons Neck, SC.

The family ties of the Foys and those families kept in bondage remained tightly woven between and among and through multiple generations of white Foy family descendants and those families of the enslaved. To keep accumulated wealth within geographical and agricultural patterns, southeastern NC planters made a practice of marrying sons and daughters to neighboring planters with similar crop valuations. Routinely, newlyweds of planter families were provided a dowry of enslaved people from respective families, so the younger newly apprenticed and oftentimes oldest members of the enslaved could more readily establish new households and assume the agricultural duties of a gifted portion of the estate.

Leading up to Abraham Lincoln’s presidential nomination for the Republican Party, Joseph Mumford Foy held fast to his Unionist ties, the foundation of which were built upon the family’s active participation and service during the Revolutionary War. While North Carolinian planters hotly debated the role of the Federal government in determining the emancipation of enslaved Americans, parts of the South were already discussing succession. After Ft. Sumter, South Carolina was fired upon by Confederate militia on April 12, 1861, North Carolina was the last Southern state to join the Confederacy on May 1, 1861.

In the October 2013 issue of Our State, Burial and Mourning at Poplar Grove by Philip Gerard, highlights the role of Joseph Mumford Foy’s wife, Mary Ann Simmons Foy during the Civil War. Her Unionist allegiance in honor of her dead husband and in service to her nation stood steadfast in the face of opposing forces. Her recently deceased husband had declared “Union forever” in a letter to their eldest son, David, during the fall Presidential election campaign of Abraham Lincoln, a contradiction of political and social ideas among the coastal planters who owned slaves but had strong ties to the Revolutionary War.

Notably, the enslaved people of the Foy family as well as the enslaved communities of neighboring planters knew intimately the shoreline, creeks, swamps, riverbeds and estuaries of the Cape Fear, and thus excellent pilots, boatmen and fishermen. However, the skills and talents of the enslaved people of Poplar Grove are best reflected in the successful cultivation of peanuts and sweet potatoes in the sandy loamy coastal soil, and though rarely recognized, were the engineering and artisan skills of the enslaved males who constructed the current manor house from on-site materials circa 1850-1853. The mill pond that still lies within the Abbey Nature Preserve and accessed by the original farm road that cut through the fields help to produce most of the construction materials.

From foundation to rooftop to the interior of the home’s horsehair plaster walls & crown molding to the heart pine floors and black walnut staircase, the three-story manor house stands today as a testament to these little recognized individuals who, like the neighboring plantations along the coastal highway of North Carolina, are part of the Gullah Geechee Corridor with its revolutionary roots leading up to Civil War through the Wilmington Race Massacre of 1898, the Jim Crow Movement of the early 20th century and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s.

Within the museum complex is the original smokehouse, kitchen shed, carriage house, and the last remaining tenant house belonging to Nimrod Nixon, whose brother Cleveland Nixon is pictured at the top left of this page. Nimrod Nixon served in WWII, at the same time his employer son’s, Robert Lee Foy, Jr., served. Mr. Nixon returned to Poplar Grove after the war and lived in the surviving tenant house without running water and electricity until the late 1950s when Robert Lee Foy, Jr. inherited the farm lands, outbuildings and manor house of Poplar Grove from his father, Robert Lee Foy, Sr.

Three heritage art studios are on site for viewing: the Basket Gallery, the Print Shop and Blacksmith Shop, in addition to an Agricultural Exhibit housing a peanut thrasher and information on the production of peanuts and the Gullah Geechee peoples. This space is currently being expanded to include more specific information regarding the tenant families whom remained on site through WWII.

The Foundation would like to thank Dr. Kimberly Sherman, consulting historian, for conducting early research and providing historical and political context to the Foy family archives located both on the property and in the Robert Lee Foy Collection at the Joyner Library at East Carolina University as well as Beverly Smalls, Bertha Todd, and Karene Manley for their invaluable input, and the ongoing research of the enslaved and their descendants by Caroline C. Lewis, Executive Director.

We are honored to exhibit, From Civil War to Civil Rights: The African American Experience at Poplar Grove, which opened on June 19, 2014. This permanent display is free to the public and located in the lower level of the Manor House. The project was made possible in part by funding from the North Carolina Humanities Council, a statewide non-profit and affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

From Civil War to Civil Rights from Poplar Grove on Vimeo.