Slavery and Emancipation at Poplar Grove

The Seaborne Slave Trade of North Carolina from the North Carolina Historical Review reports that slaves imported to North Carolina prior to the Revolution from extant records came mainly from the West Indies, most particularly Montego Bay, Jamaica; Barbados; Antigua; and the Bahamas; a small number from mainland colonies; and an even smaller number directly from Africa, though imports between the years 1772-1775 rarely exceeded 150 slaves annually (Minchinton).

Slaves arriving from the West Indies to the Carolinas were considered well-seasoned, or rather broken in mind, body and spirit to the permanent conditions of slavery in the New World, both like and unlike the practices of slavery on the African continent between warring and rival tribes. Most of the imported slaves from the West Indies “spoke English, had been born or lived in the sugar islands and understood European customs and culture. For them the adjustment to the New World proved less traumatic than that of later generations of newly imported Africans” (Kay 12).

However, “By 1771 fully 62 percent of the slaves in North Carolina lived on plantations with ten or more slaves. Such a concentration of slaves had one salutary effect for blacks. It allowed them to create a black community and interior life separate from the strict oversight of whites and to develop concomitantly a collective consciousness to lighten slavery’s oppression” (Crow et al. 11). “Thus while only 31% of the families of North Carolina held slaves in 1790, the concentration of slaveholders and slaves appeared in counties where tobacco, rice and navel stores prospered. Both Warren and New Hanover counties, for instance, averaged 10.3 slaves per slaveholding family, while Halifax ranked next with 8.7. Randolph County, on the other hand average only 3.5” slaves per slaveholding family (Crow 6).

Colonial methods of the cultivation of crops and gardens was considered “crude, unscientific and wasteful” by the English and Europeans. The well-circulated American Husbandry, “complained, for example, that North Carolinians were ‘spoiled for good husbandry by plenty of land.’ They failed to rotate or fertilize crops on a systematic basis, and they left fields unweeded. And North Carolinians, supposedly, unlike Virginians, did not manage their tobacco ‘with any spirit.’ This generally ‘careless manner’ characterized the handling of livestock as well. Cattle and hogs roamed free, and because there was an ‘almost total neglect of inclosure,’ they frequently trampled crops” (Kay 35). Poplar Grove’s slaves and later tenant farmers carried on these traditions well into the 20th century, so that Jersey cows roamed freely and hogs were set loose to turn over the fields after the peanuts had been harvested.

Such loose practices were both a product of the overwhelming expanse of coastal lands populated by long-leaf pines, cypress and gum forests that required clearing, but also a part of the traditions and specific skills of imported slaves prior to the Revolution. “Africans who entered this world confronted a situation not wholly unfamiliar from their own concepts of time and labor … and brought with them a task-oriented conception of work” (Kay 35). Furthermore, and not unlike the management practices of plantations populated along the coastlines of the Carolinas, “West Africans also shared with them a notion of time as dictated by the seasons, natural phenomena such as the phases of the moon, and the harvesting of particular crops” (35).

Of the written references to the brutality of slave labor and the cruel punishments for disobedience, observations were also noted in letters and journals that masters were often seen working alongside their enslaved and indentured servants, particularly in North Carolina rather than the more refined agrarian practices of the tobacco and rice plantations in Virginia and South Carolina, respectively.

One German traveler in the 1780s remarked while stranded in Edenton, NC, that “No people can be so greedy after holidays, as the whites and blacks here, and none with less reason, for at not one time do they work so as to need a long rest. It is difficult to say which are the best creatures, the whites here or their blacks, or which have been formed by the others, but in either case the example is bad. The white men are all the time complaining that the blacks will not work, and they themselves do nothing” (Crow 14).

From Slavery in North Carolina, “The ban on importing slaves to North Carolina was lifted in 1790, and the state’s slave population quickly increased. By 1800, there were around 140,000 blacks living in North Carolina. A small number of these were free blacks, who mostly farmed or worked in skilled trades. The majority were slaves working in agriculture on small- to medium-sized farms. As in the colonial period, few North Carolina slaves lived on huge plantations. Fifty-three percent of slave owners in the state owned five or fewer slaves, and only 2.6 percent of slaves lived on farms with over 50 other slaves during the antebellum period. In fact, by 1850, only 91 slave owners in the whole state owned over 100 slaves.

Because they lived on farms with smaller groups of slaves, the social dynamic of slaves in North Carolina was somewhat different from their counterparts in other states, who often worked on plantations with hundreds of other slaves. In North Carolina, the hierarchy of domestic workers and field workers was not as developed as in the plantation system. There were fewer numbers of slaves to specialize in each job, so on small farms, slaves may have been required to work both in the fields and at a variety of other jobs at different times of the year. Another result of working in smaller groups was that North Carolina slaves generally had more interaction with slaves on other farms. Slaves often looked to other farms to find a spouse, and traveled to different farms to court or visit during their limited free time” (LearnNC).

On the eve of the American Civil War, the enslaved comprised nearly one-third of North Carolina’s population. Enslaved, numbering more than 331,000 in 1860, made up the state’s lowest social class. While they were held in all counties, slaves maintained a higher presence in the eastern portion of the state where the environment lent itself to intensive agricultural pursuits. Most enslaved men were engaged in the production of cash crops, particularly tobacco, cotton, indigo, and rice. In New Hanover County alone, 7,103 enslaved men, women and children were counted in 1860.

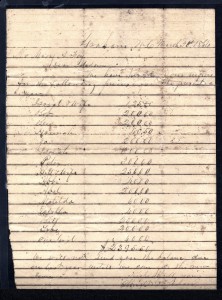

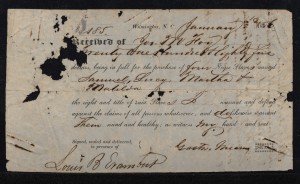

Slavery was also an investment. About fifty percent of all southern wealth in the antebellum era was held in slaves. While Joseph Mumford Foy inherited most his slaveholdings through the last wills and testaments of his mother and father as well as his marriage to Mary Ann Simmons Foy, surviving slave receipts from the Robert Lee Foy Collection estate indicate that he spent between 1850 and 1860 at least $14,793 at an average cost of $704 per slave with the purchase of Leah in 1851; Alfred and Joseph in March 1854; Ben in February of 1855; Williams in March 1855, then William in April 1855, then Robert in December 1855; Samuel, Lucy, Martha, Matilda (see slave receipt to the right) on January 2, 1856 for $2,185.00 as well as Tobey, who was purchased separately that same month and year; Nancy, Daniel and Nathaniel belonging to the estate of A. Mashburn in January 6, 1857 (Slave_Tree_Nathaniel Foy Notes) as well as Hannah in January 1957, about 11 years old; Sealy and Ellen from Joseph Jones, date unclear; Celia in June 1857, then Elcy in September 1857 from George Ward of Onslow County, for $403.00; Jere Nichols on October 11, 1858; and finally, Bill, about 18 years old, on January 13, 1859 from his brother, Hiram W. Foy, for $1000.00, a considerable sum.

Slavery was also an investment. About fifty percent of all southern wealth in the antebellum era was held in slaves. While Joseph Mumford Foy inherited most his slaveholdings through the last wills and testaments of his mother and father as well as his marriage to Mary Ann Simmons Foy, surviving slave receipts from the Robert Lee Foy Collection estate indicate that he spent between 1850 and 1860 at least $14,793 at an average cost of $704 per slave with the purchase of Leah in 1851; Alfred and Joseph in March 1854; Ben in February of 1855; Williams in March 1855, then William in April 1855, then Robert in December 1855; Samuel, Lucy, Martha, Matilda (see slave receipt to the right) on January 2, 1856 for $2,185.00 as well as Tobey, who was purchased separately that same month and year; Nancy, Daniel and Nathaniel belonging to the estate of A. Mashburn in January 6, 1857 (Slave_Tree_Nathaniel Foy Notes) as well as Hannah in January 1957, about 11 years old; Sealy and Ellen from Joseph Jones, date unclear; Celia in June 1857, then Elcy in September 1857 from George Ward of Onslow County, for $403.00; Jere Nichols on October 11, 1858; and finally, Bill, about 18 years old, on January 13, 1859 from his brother, Hiram W. Foy, for $1000.00, a considerable sum.

Prior to and during the construction of the Manor House, between the years 1847-1851, Joseph Mumford Foy continued to acquire slaves, of which every attempt has been made to locate historical records for specific dates, names, and ages. More specifically, and not yet fully cross-referenced with the above slave receipt records and his last will and testament, The Slave Deeds of New Hanover County record Joseph Mumford Foy as purchasing Dilcy on October 29, 1847, from the estate of David W. Simmons from Onslow County, for $560.00; in January 1848, Maria and her two year old child, Charles Henry, from Richard Bradley of Wilmington; on March 1, 1849, two slaves by the names of Isah/Isaiah and Berthy from John B. Wright; from Nicholas N. Nixon, Nancy and David as well as Nathaniel were purchased on January 3, 1851, then in February 1851, a female named Leah (as previously referenced); from Samuel Nixon, a group of ten notable Wilmington gentlemen, including Nicholas Nixon and Joseph Mumford Foy, purchase Hannah Nixon, Eliza Nixon, Penny Nixon, John Nixon, Amy June/Amy Lane, and Milly Jane/Milly Lane on March 30, 1853 – circumstances unknown.

However, less than two years later, Samuel Nixon then reclaims these very six enslaved persons on September 19, 1855 from nine of these same gentlemen, excluding Joseph Mumford Foy. It is assumed there was a “gentlemen’s agreement” between Samuel Nixon to borrow money via the sale of his enslaved that would then be recouped once he could secure the funds to repurchase them. What role and why Joseph Mumford Foy was included in the purchase but not the sale of these enslaved is unclear, as 1855/56/57 proved to be a well-spring of activity for increasing the number of enslaved at Poplar Grove.

On April 12, 1855, Joseph Mumford Foy purchases Williams (referenced previously) from Mr. A Smith; later that same year, on November 24, 1855, he purchases from his brother, Hiram W. Foy, a male slave named Jack; only weeks later, he purchases Robert from Mr. O. Burgess on December 11, 1855; and within a month, he purchases Toby/Tobey (referenced previously) from Joseph Mayes on January 2, 1856; months later, on March 13, 1856, he returns to Mr. A. Smith to purchase Alfred and Joseph (referenced previously); less than a year later, from Archibald Murdock McKinnon, he purchases Nancy, Harry, Stoke and Roxanne on January 14, 1857; two months later, he purchases a male named David on March 10, 1857, from Williams Bryan; later that same year, he purchases Elcy (mentioned earlier) on September 1, 1857 from the estate of George Ward, trustee Andrew J. Johnston; and lastly, on February 10, 1858, he purchases Patsey from Nicholas N. Nixon.

Notably, The Slave Deeds of New Hanover County is an extensive list of the enslaved purchased and sold dating as far back as 1743 in New Hanover County. When James Foy, Jr. appears in the records, it is for the purchase of Hannah and an unnamed person from Edward St. George on March 6, 1809. Unlike many planters nearby, between 1809 and the Civil War, Joseph Mumford Foy is recorded as having sold only one of his enslaved, a female named Maria (referenced previously) and unaccompanied by her little boy, Charles Henry (referenced previously), to John Cowan, Sr. on February 25, 1849.

Slaveholdings were a sign of wealth and power in the antebellum South. The Foy family belonged to a large planter class network in the community of Scotts Hill and the city of Wilmington. In 1860, Joseph M. Foy owned fifty-nine enslaved persons. The Foys were part of a well-established centuries-ruling planter class. Out of 938 slaveholders in the county, only 21 planters owned more than fifty enslaved persons, including children. By comparison, 744 of the 34,658 slaveholders in North Carolina owned more than fifty slaves. The Foys, therefore, remained in the top 2% of the slave-holding group.

The plantation complex at Poplar Grove looked looked very different from the lawns and outbuildings we see today. A highly organized and efficient layout of outbuildings, including blacksmith shop, orchards, hog pens, corn cribs, milk house, buggy shed, and barn intersected the landscape with straight lines and right angles, while a large hog killing yard was located behind the existing root cellar and kitchen.

The sixteen slave quarters listed on the 1860 Slave Schedule for Joseph Mumford Foy were most likely comprised of early older cabins closer to the original homestead and further out in the fields, while newer cabins from the 1850 construction of the manor house were most likely located to the rear of the current barn, far enough away from the manor house, but still within reach of supervision. Housing of newer construction also existed closer to the manor house and outdoor kitchen for enslaved domestics, buggy and carriage drivers, and the blacksmith. Such dwellings were most likely double cabins constructed in a similar manner to the surviving tenant house and indicated their higher status among the community of enslaved. A three-hold necessary within a clapboard frame was next to the outdoor kitchen.

The enslaved at Poplar Grove held many roles on the plantation. Domestic servants cooked, cleaned, washed, ironed, and cared for the daily needs of their enslavers. Skilled male artisans such as carpenters, plasterers, brick-masons, and blacksmiths constructed and maintained the manor house and outbuildings, and when necessary joined a number of enslaved on the day to day operation of field work, plowing, seeding, and later harvesting peanuts, sweet potatoes, and other such crops.

About half of the enslaved reported on the Federal Slave Schedule of 1860 were under the age of sixteen. Many of these enslaved children cared for their younger siblings until old enough to work in the fields (around age 12) and performed small tasks such as caring for chickens, tending garden patches, or apprenticing under the supervision of a mother/father or uncle/aunt whose duties and responsibilities were directly related to the needs of their enslavers and highly skilled in nature, i.e. blacksmith, weaver, cook, driver, cooper, etc.

The Foys were active Methodists and founding members of the Wesleyan Chapel United Methodist Church at Scotts Hill, but the enslaved at Poplar Grove did not have a house/building specifically designated for worship. Mary “Maudie” Hines, a former enslaved, communicated that the community of enslaved were not allowed to gather in groups to pray, and instead “prayed in pots” – a Gullah practice of ensuring prayers were not overhead by enslavers.

Southern planters were often wary of the possibility of conspiracy when groups of the enslaved gathered together, especially so close to the sounds and estuaries of the Atlantic Ocean. “The presence of a coastal escape route was widely known in tidewater slave communities, among merchants and planters who went to great lengths to control it … Wilmington, the largest port in antebellum North Carolina, had a special reputation, in the words of a Rocky Point planter, as ‘an asylum for Runaways’ because of its location near the mouth of the Cape Fear River, its steady sea traffic, its strong ties to New England, and its black-majority population” (Celeskit 124).

Enslaved communities, therefore, chose to subvert the system of slavery by stealing away to the woods to worship in their own way. “Though discovery meant severe punishment, slaves often slipped about surreptitiously in the evening hours, visiting friends and family on other plantations, worshiping, courting, hunting, fishing, and trading illicitly. Those nocturnal forays not only sharpened their ability to dodge slave patrols but also stretched the boundaries of their bondage by identifying blind spots in the vigilance of their owners” (Celelski 127).

Other than clandestine methods of escape, a form of psychological control and oppression was hope and fear – the promise of being set free, or the threat of being sold. Manumission, the process to free a person enslaved, would have been very difficult and expensive for a planter in North Carolina due to a state law passed in 1830. Manumission, under state jurisdiction, required enslavers to provide two $1,000 security bonds and ensure that the freed slave leave the state within ninety days. It would appear that Joseph Mumford Foy employed the promise of being set free, as he did not make a practice of selling his enslaved, and seeks to ensure that such a practice continues even after his death, stating in his last will and testament that “no negro is to be sold unless he becomes unmanageable or shall be guilty of some vicious habit.”

Even though the Foys were Methodist and the Methodist church was historically associated with the anti-slavery movement, southern Methodists who were divided over the issue chose to form the United Methodist Church-South in 1845 and the local Scotts Hill congregation followed suit.

When Joseph M. Foy died in March 1861, two weeks shy of the south’s secession, an inventory was completed of his estate. This inventory included a list of the first names of the fifty-nine enslaved men, women, girls and boys compromising family units by blood or necessity of mothers, brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles and cousins:

“John, Rachel, Leah, Jo, Winslow, Izah/Israel, Big Leah, Betsy, Kitty, Ruth, Isaac, Peter, Caroline, Abel, London, John, Alice, Katherine, Stella, Mary, Sarah, Mariah, Cornelia, Abby/Abbe, Margaret, Alice, Ben, Alfred, Jo, William, Adaline, Jere, Paul, Henrietta, Bob, Sam, Lucy, Matilda, Toby, Fannie, Hannah, Snow, Daniel, Nathan, Ellen, Dave, Patsy, Dinky, Bill, Ida/Ada, Frank, Simon, Jim, Josh, Bernard, Jo, Hannah, Jane, Sallie, and Celia”

Upon the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the Foy enslaved remained at Poplar Grove and were managed by an hire overseer from the Nicholas Nixon plantation in 1862 and 1863. Later, seventeen slaves, including Israel and his wife; Bob; Ben; Hannah; Jo; Isaiah; Peter; Bill and wife; Abbi; Abel; Matilda; Stella/Estella; Bill; Toby; and one girl were rented out and sent to the NC interior for a planter named Benson in Graham, NC, near Chapel Hill, in 1863 and 1864 for $2,395.50.

In 1864, with a portion of the enslaved rented out, the management of the plantation was skeletal, and likely operated by those enslaved men, women and children that were specifically chosen to remain on site. Researched shows that Mary Ann Simmons Foy took her young children and a few of her enslaved domestics to Sampson County, demonstrating her belief that the property will remain under the management of those enslaved she entrusts to oversee continued operations of the “farm.”

Upon return to her family home, which is left unspoiled by the war, Mary Ann Simmons Foy, “an invalid” by all accounts, supervises Poplar Grove’s transition from plantation slavery to tenant farming until her death in 1875. Her second surviving son, J.T. would establish himself as proprietor and manager during the latter part of Reconstruction.

While evidence does not indicate that any of the Foy’s enslaved attempted self-emancipation during the Civil War, Winslow Nixon, an enslaved male at Poplar Grove, will enlist in the 14th Regiment of the US Color Troops in New Berne, NC, in 1864, while Wilmington and the surrounding area experience significant social upheaval during the conflict. The Wilmington Daily Journal posts on November 28, 1861:

“Look Out. — Negroes occasionally steal boats and make their way to Yankee blockading vessels outside. We mention this to put the owners of boats on the sounds or at the mouth of the river on their guard, so that their boats may be properly secured.

We understand that on last Monday night, between ten and twelve o’clock, three boys, one belonging to Jas. N. Craig, another to James S. Newton, and a third to Miss Mary Newton, stole a boat belonging to Joseph Burris and made their way in her to the blockaders off Confederate Point. The boy belonging to J. S. Newton is well posted about every thing on the point, having been at Fort Fisher since it was first commenced. He can, and no doubt will, give the enemy much information, so that our officers should bear this fact in mind. This fellow has n o doubt listened carefully to all that has been said, and being a keen, intelligent fellow, has made use of it by treasuring it up. Thee is the greater reason for care and circumspection.”

William Benjamin Gould, an artisan slave from the neighboring peanut plantation owned by Nicholas Nixon, and notably worked on the Bellamy Mansion during its construction, escaped while hired-out in the city of Wilmington in October 1862. He and seven other slaves stole away under the chaos of the yellow fever epidemic which plundered the city that fall. William Gould’s artisan skills can be seen in the plaster of Paris work of both the medallions and crown molding in the Bellamy Mansion. The patterns of one plaster of Paris medallion at the Bellamy is modeled after the two formal parlor medallions at Poplar Grove, a likely indication that William Gould was apprenticing during the construction of the manor house at Poplar Grove – a testament to the valued skills of a few notable artisan slaves, which no less underscored their desire to be free.

Another instance was recorded by Private John C. Fennel, a Confederate soldier stationed at Camp Heath in Scotts Hill. Due to the presence of Union soldiers as far south as White Oak Swamp in neighboring Onslow County, many slaves were escaping to Union lines and being kept as “contraband of war.” Fennel noted that a group of Confederate soldiers disguised themselves as Union troops and lured a group of slaves into their encampment, only to dash their hopes of freedom. The willingness of these slaves to follow indicates that not all slaves were happy with their status in the “peculiar institution” and sincerely hoped for the extension of liberty to their families.

President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation into law in 1863, declaring “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” The Wilmington Daily Journal posted an announcement on February 7, 1863:

“Slaves every day make or attempt to make their escape to the Lincoln Blockaders. Any slave caught so attempting, ought to be hung on the nearest land to the point where caught. Any white man convicted of aiding or abetting, ought to share his fate. Things of this kind must be stopped by some acts of apparent but necessary vigor. The country can better afford to pay for a few exampled than it can allow the citizens to be betrayed and plundered.”

Freedom was not fully extended to the enslaved in New Hanover County until the fall of Wilmington and the surrounding area to the Union Army in February 1865. Few opportunities presented themselves for the former enslaved and state laws, such as the Black Codes, attempted to control the mobility of African Americans. Many freedmen faced the choice of destitution or working for their enslavers as tenant farmers or sharecroppers.

Several former Poplar Grove enslaved men and women remained on the plantation as tenants while choosing surnames to denote their new status and solidified family bonds that had been well-established between enslaved communities among the coastal plantations between Sloop Point/Topsail Sound and Scotts Hill/Rich Inlet for two centuries. Rachel and Leah chose the surname Sidberry/Sidbury, while Leah’s son, Abel, chose the surname St. George. These planter surnames reflect how the relationships between the enslaved of neighboring plantations often crossed property boundaries: Foy, Nixon, Sidberry, St. George, Everitte, Moore, Burgywn, Williams, Hansley, Howard, Shepard, Carr, Picket, Rhodes, Burn, Alexander, Johnson, and Reddick.

By 1870, freedmen (10,462) outnumbered Wilmington’s white (6,888) population (33). The hard-won economic and political successes of an emerging African American middle class only fueled the end of the Reconstruction era. “The Democratic Party emerged from Reconstruction wholly solidified behind the concept of native white rule within the government against the picture it painted of the Republicans as a party represented by northern carpetbaggers and illiterate former slaves” (29).

In the case of Bartlett_v_Strickland, “Conservatives in the NC General Assembly sought to isolate the influence of Republicans and African Americans in New Hanover County by taking the northern two-thirds of the county and forming Pender County” (8). Thus, the formation of Pender County in 1875 effectively separated Scotts Hill and the Foy family household from New Hanover County in attempt to push out the African American vote.

However, Wilmington was still a destination point for rural freedmen to begin an economic life and those in the skilled trades could find a niche in the city of Wilmington. “The African American population of Wilmington prospered and by the 1880s had a complex society. Regular celebrations of Emancipation Day and Memorial Day were spectacles with parades and speeches by both blacks and whites.

Included in a report from the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission, “Wilmington’s African American population saw some gains in political office, but the area in which they saw the greatest advance was business … including shoemakers, carpenters, painters, masons, butchers, teachers, blacksmiths, barbers, wheelwrights, mechanics, and grocers” (32). Like other cultural groups in the city, African Americans developed literary societies, built libraries, established benevolent organizations to provide for the needy and developed baseball leagues. Along with creating new traditions, Wilmington blacks continued a few traditions developed under slavery, such as the Christmas Day Jonkonnus” (“1898” 30).

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, J. T. Foy and his younger brother, Francis Marion Foy, continued management of the fields surrounding Poplar Grove with the labor force of tenant farming families living on site that had descended from former Foy slaves and slave descendants from neighboring farms and plantations with a degree of success best reflected in high crop yields and their investment in the railroads. As the aging slave cabins collapsed, single and double-sided tenant houses were built close behind the Manor House and between the Manor House and western perimeter of the fields commonly referred to as “the lot.”

Francis Marion Foy observes the growth of his cornfield at Scotts Hill. Pictured are George Nixon holding Cleveland Nixon, 1896.

Nora Foy Brown recalls that “There used to be a lot of houses back in there where the tenants used to live … it was Ms. Mary Jackson and Mr. Israel (Jackson), Ms. Cornelia Durham, Ms. Lily Durham, Ms. Pearson, what was her last name? Ms. Shue, we called her Aunt Shue, and … there was a lot of … and Uncle Talon/Talton, an old man named Uncle Talon, he’s a a old bachelor. He brought in all the wood and the water upstairs” and greatly assisted Mrs. Nora Foy, J.T.’s wife.

The 1900 Census lists the members in Israel Jackson’s household – click here: 1900 Census Israel Jackson. The record indicates also lists the household of Francis Marion Foy on the same page as well as Israel Jackson and his wife Mariah whom he married in 1896 when he was about twenty-three years old. The couple had a boy named Edward, who is noted as being three years old.

However, as it turns out, Uncle Talton was not a bachelor. He had married Mary Eliza Taylor, who worked for Mrs. Nora Foy until her death in 1921, after which Mary Eliza marries Israel Jackson. Nora Foy Brown remembers from her childhood that Uncle Talton remained a bachelor the rest of his days, while continuing to live and work with Israel Jackson and Ms. Mary Liza at Poplar Grove. The couple lived in a white clapboard house with glass windows and green shutters, of which Nora Foy Brown remembers that Israel and Mary Liza raised two adopted children and remained on site in the white clapboard house until they both died. The house was still standing in 1979 and later demolished from disuse.

This page is continually being updated. Please visit our page on Tenant Farming.

References & Further Reading

Cape Fear Community Colleges Library. New Hanover County Slave Deeds. http://libguides.cfcc.edu/deeds

Crow, Jeffrey J. The Black Experience in Revolutionary North Carolina. Raleigh, NC: Division of Archives and HIstory, NC Department of Cultural Resources, 1977, 2001.

Crow, Jeffrey J., Paul D. Escott, and Flora J. Hately Wadelington. A History of African Americans in North Carolina. Raleigh, NC: Office of Archives and History, NC Department of Cultural Resources, 2011.

Genovese, Eugene D. Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York: Vintage Books, 1974.

Gould, William Benjamin. Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor. Stanford University Press, 2002.

Historical Census Browswer, University of Virginia Library. http://mapserver.lib.virginia.edu

Kay, Marvin L. Michael and Lorin Lee Cary. Slavery in North Carolina 1748-1775. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

LearnNC: North Carolina Digital History. UNC School of Education. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-antebellum/

Learn NC: North Carolina Digital History. UNC School of Education. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-newnation/5252

Robert Lee Foy Collection. Joyner Library. East Carolina University. Greenville, NC.

Reaves, William. Strength through Struggle: The Chronological and Historical Record of the African American Community in Wilmington, North Carolina, 1865-1950. New Hanover Public Library, 1998.

Soley, James Russel. The Navy in the Civil War. http://usnllp.org/OurNavy/section_I_chapter_IV.html

Watson, Alan D. Wilmington, North Carolina to 1865. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2003.

White, Deborah Gray. Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1999.

Wood, Bradford. This Remote Part of the World: Regional Formation in Lower Cape Fear, North Carolina 1725-1775. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2004.