Poplar Grove Plantation, as part of the National Register of Historic Places and as part of the Gullah Geechee Corridor established by the National Park Service, reflects the traditions of a diverse community of enslaved people in southeastern North Carolina, and in particular what then became Pender County during the Reconstruction Era.

Poplar Grove Plantation provides a culturally rich opportunity to explore local and regional Gullah Geechee history as it relates to the enslaved families whose agricultural practices, including the cultivation of indigo, peanuts, and sweet potatoes, enriched their white enslavers to both acquire more land and more enslaved people to work that land. For those plantations south of Wilmington, most notably Orton Plantation, enslaved Gullah communities produced rice, or Carolina Gold, while north of Wilmington, enslaved communities produced peanuts, referenced in early Colonial histories as “ground peas,” to supplement the diets of the enslaved communities up and down the Gullah Geechee Corridor.

In addition to their cultivation skills in rice and indigo, West Africans also brought with them exceptional heritage arts skills, such as basketry, weaving, metalsmithing and blacksmithing, and directly contributed to the cultural development and economic sustainability of southeastern North Carolina. (Visit the North Carolina Rice Festival in Winnabow, NC, “Celebration through Education” event in March 2026 and the Ocean City Jazz Festival on Topsail Island, NC in July 3-5, 2026).

Linking the history of the Foy family of Poplar Grove with the history of the Gullah during enslavement and afterwards offers a lens through which to view the daily practices of a plantation site that was established by Cornelius Harnett as an indigo plantation and himself, along with John Burgywn, among one of the largest importers of slaves to this area via Charleston, South Carolina. The cultural, agricultural, and religious practices of the enslaved by the Foy family and their descendants were passed down from generation to generation, a practice once referred to as “natural increase,” and dates back to the British Colonial period of the Carolinas, through the American Revolution, Civil War, and later, the Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and Civil Rights eras.

Through the efforts of the National Park Service to establish this Corridor, “the Gullah Geechee story represents a crucial component of local, regional, and national history. Preserving and interpreting Gullah Geechee culture and its associated sites is significant to people of all racial, regional, and ethnic backgrounds and is vital to telling the story of the American heritage” (NPS 2). Only recently has Pender County, North Carolina, and St. Johns County, Florida, been included in the expansion of the Corridor.

What is the Gullah Geechee Corridor?

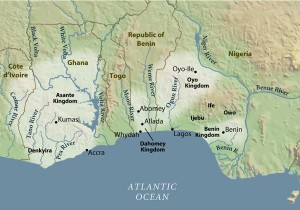

“The Corridor represents a significant story of local, regional, national, and even global importance. The Corridor encompasses a cultural and linguistic area along the southeastern coast of the United States from the northern border of Pender County, North Carolina, to the southern border of St. Johns County, Florida, and 30 miles inland. This area is home to one of the country’s most unique cultures, a tradition first shaped by enslaved Africans brought to the southeastern United States from the primarily rice-producing regions of West and Central Africa” (GGCHCC 8).

Who are the Gullah Geechee People?

“Gullah Geechee ( \ˈgə-lə\ \ˈgē-chē \ ) people are direct descendants of Africans who were brought to the United States and enslaved for generations. Their diverse roots in particular parts of Africa, primarily West Africa, and the nature of their enslavement on isolated islands created a unique culture that survives to the present day. Evidence of the culture is clearly visible in the distinctive arts, crafts, cuisine, and music, as well as Gullah Geechee language. The culture is embodied in diverse patterns of social organization reflecting the intimate and private ways communities and families meet the challenges of life.

The culture is manifested in a system of practices/principles that emerge from: (1) the diverse African origins of Gullah Geechee peoples, (2) intense interaction among people from different language groups, and (3) generations of isolation in settings where enslaved Africans and their descendants were the majority population. The isolation continued after the Civil War ended in 1865. A hostile society led Gullah Geechee communities to remain unto themselves for almost another century. Customs, traditions, and beliefs continued to develop, often in opposition to segregation and oppression from the dominant society” (GGCHCC 5).

Guinea Coast, 1600-1600 A.D.

The heritage arts most associated with the Gullah Geechee culture include basket-making, weaving and blacksmithing. Trade Relations among European and Africans, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, notes that as early as the 15th century, and “Contrary to popular views about precolonial Africa, local manufacturers were at this time creating items of comparable, if not superior, quality to those from pre-industrial Europe. Due to advances in native forge technology, smiths in some regions of sub-Saharan Africa were producing steels of a better grade than those of their counterparts in Europe, and the highly developed West African textile workshops had produced fine cloths for export long before the arrival of European traders” (www.metmuseum.org).

“The coasts of North Carolina possessed a unique slave culture and economy. Numerous jobs on the coast were filled by slave labor. Slaves were used as sailors, pilots, fishermen, ferryman, deckhand, and shipyard workers. The coast also provided many opportunities for slaves to escape. Many advertisements, such as this one from the State Gazette of North Carolina , published in Edenton on February 2nd, 1791, warned “All masters of vessels are forbid harbouring or carrying them [slaves] off at their peril.” Many slaves who attempted to escape via the waterways traveled to port towns such as Wilmington, Washington, or New Bern” (Winer, Samantha). http://libcdm1.uncg.edu/cdm/history/collection/RAS#ftnt21

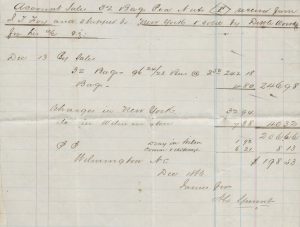

The following is taken directly from: Minchinton, Walter E. “The Seaborne Slave Trade of North Carolina.” The North Carolina Historical Review. Vol. 71, No. 1 (JANUARY 1994), pp. 1-61. North Carolina Office of Archives and History.

“For North Carolina, like other American mainland colonies, Negroes could be obtained by sea from three sources: Africa, the West Indies, and other mainland colonies. The story of the seaborne slave trade to North Carolina falls into three periods: first, the years to 1748, when a small number of blacks were brought in for domestic purposes; second, the period from 1749 to the American Revolution, when a growing number of slaves were imported, particularly to cultivate rice in the moist lowlands of North Carolina from the lower Cape Fear River south; then, after the Revolution interrupted imports, the final years of the trade until 1790, when slaves were brought in for plantation cultivation.

The one exception to that pattern—and it was an enormous one—revealed the importation of 258 Negroes directly from Africa in 1759.

During the Stamp Act controversy, 1765-1766, the colonists forced the resignation of several officials, including the comptroller of Port Brunswick, which was closed for several months. That action may have affected the trade in slaves. But the agreement of North Carolinians, like other colonists, to boycott slave imports starting November 1, 1765, seems to have had little effect on the trade in slaves.

Moreover, ‘a Parcel of likely healthy slaves’ from Africa arrived in New Bern on the schooner Hope in 1774. The latter shipment may have reflected an emerging interest in trade with Africa. Taken together, the extant registers plus a few other records show that imports of slaves into North Carolina were at least 112 in 1772 and exceeded 117 in 1773 and 258 in 1774, with smaller imports in 1771 and 1775. The small size of consignments of slaves shipped from the islands of the West Indies suggests that they were sent as partial payment for the cargoes of lumber, provisions, and livestock carried thence. The exports from North Carolina rather than the demand for slaves provided the impetus for that trade.

The political and military tumult of the revolutionary war effectively ended the slave trade to North Carolina

Unlike most of the new American states that outlawed the slave trade in Negroes after the Revolution, the import of slaves by sea was resumed in North Carolina, as the shipping registers that survive for all five customs ports for most of the 1780s reveal.

A total of 993 blacks are known to have been brought to North Carolina between 1784 and 1790. The largest single source of supply was Charleston, from whence came 261 slaves (26.3 percent); 212 (21.3 percent) came from the West Indies, mainly from Jamaica; three large consignments totaling 231 (23.3 percent) came from Africa; and 273 (27.5 percent) came from other mainland states …

The slave trade was too small to support the existence of specialized slave merchants, so those who imported slaves into North Carolina were general merchants. Among the prominent merchants at Wilmington who engaged in the slave trade in the third quarter of the eighteenth century were Frederick Gregg, John Burgwin, and Cornelius Harnett” (“The Seaborne Slave …”).

How has Gullah culture impacted Poplar Grove?

Cornelius Harnett purchased land at Rich’s Inlet from Ann Moore in 1707 to build a 2nd plantation home to wait out the summer months, as did many of the British colonial planters of Rocky Point with homes along the Northeast branch of the Cape Fear River. The plantation produced indigo and maize corn from a population of primarily enslaved men until the property was purchased by Francis Clayton after Cornelius Harnett succumbed to his demise in 1781 after being taken prisoner by British Loyalists during the Revolutionary War. After the war, Francis Clayton, as a Scottish Highlander, returns to England, and the property is listed for sale in 1791and purchased in 1795 by James Foy, Jr., the son of Captain James Foy, Sr. of New Bern, who had served at Moore’s Creek Battlefield, under the NC militia as part of the county regiments of the New Bern Distract Brigade.

Interpreting and displaying the history of Gullah Geechee culture at Poplar Grove has been a recent development and still underway through a re-examination of primary and secondary sources that have been quietly sitting in filing cabinets here at Poplar Grove since it opened to the public in 1980.

Briefly, Gullah influences are most represented in the agricultural production and slave management system. The Foy family, like other enslavers along the seaboard of the Gullah Geechee Corridor, employed the task system. Assignments, or tasks, were meted out each week, or to start a day, and when the assigned task was complete, typically around 2 o’clock in the afternoon, the enslaved populations has what their enslavers called “free time” to manage their private vegetable/herb garden behind their cabins, hunt, trap and fish, tend to the sick or infirmed, practice private forms of worship, or more likely, assist in helping their extended family members complete the many tasks required for the efficient operation of the plantation site, from stable yard to blacksmith shop to chicken yard to corn cribs to milk house to hog pens. This “free time” were also periods in which the enslaved with specific hire out skills could be rented to other neighboring planters. This practice included both women and men, who were oftentimes rented out to “fish camps” nestled along the shoreline. For a brief description, visit: https://networks.h-net.org/node/16821/reviews/18770/jarvis-cecelski-watermans-song-slavery-and-freedom-maritime-north

Briefly, Gullah influences are most represented in the agricultural production and slave management system. The Foy family, like other enslavers along the seaboard of the Gullah Geechee Corridor, employed the task system. Assignments, or tasks, were meted out each week, or to start a day, and when the assigned task was complete, typically around 2 o’clock in the afternoon, the enslaved populations has what their enslavers called “free time” to manage their private vegetable/herb garden behind their cabins, hunt, trap and fish, tend to the sick or infirmed, practice private forms of worship, or more likely, assist in helping their extended family members complete the many tasks required for the efficient operation of the plantation site, from stable yard to blacksmith shop to chicken yard to corn cribs to milk house to hog pens. This “free time” were also periods in which the enslaved with specific hire out skills could be rented to other neighboring planters. This practice included both women and men, who were oftentimes rented out to “fish camps” nestled along the shoreline. For a brief description, visit: https://networks.h-net.org/node/16821/reviews/18770/jarvis-cecelski-watermans-song-slavery-and-freedom-maritime-north

The primary cash crop at Poplar Grove was the cultivation of peanuts, though former historians read “ground peas” (as written in the Daily Diary of Joseph Mumford Foy and in the crop receipts) were garden or shell peas rather than peanuts, so the skills and knowledge of the enslaved peoples of the Foys and other planters supplying this food source to more extended rice and tobacco plantations were and have been traditionally overlooked because of the misinterpretation at these sites of what “ground peas” and sometimes simply “peas” were actually referencing.

As such, peanuts and sweet potatoes, just like rice, were primary crops and served as a dietary staple of the enslaved communities up and down the Gullah Geechee Corridor. Watermelons (another West African produce), blueberries and strawberries were also grown at Poplar Grove.

The enslaved community at Poplar Grove were born into, or were bequeathed among Foy siblings and their children through several generations as a way to keep this economy of wealth within the family. This is best documented through last wills and testaments and through marriages to the sons and daughters of nearby planters and merchants within a limited stretch of the corridor and, for the Foy family, traces back as early as the 1760s in Craven County, NC. The Foy family, as French Huguenots, came to the Albemarle region of the northern Carolinas by way of Baltimore and settled in New Bern. It is unknown when and how the Foys acquired slaves until they are listed on New Bern heads of household records in the 1780s as owning twenty or more enslaved between two Foy heads of household – no small number in comparison to other settlers in the region at that time.

“Despite periodic economic difficulties that plagued the city [New Bern] following the American Revolution, as well as a drop in Craven County’s white population during the 1790s (from 6,474 to 5,756), the town remained an important trading center. Even during hard times, ships loaded with tar, pitch, turpentine, lumber, and corn set sail for islands in the Caribbean, while incoming vessels, carrying manufactured goods, machinery, and slaves, arrived from New England, Europe, and Africa. New Bern was also the center of commercial activity for nearby farmers and planters who frequently visited town to conduct business, or to buy and sell various commodities” (Schweninger, Loren. “John Carruthers Stanly and the Anomaly of Black Slaveholding,” North

Carolina Historical Review 67 (April 1990):159-92).

Unlike the more notable rice, sugar, indigo and Sea Island cotton planters along the Gullah Geechee Corridor, the Foys instead appropriated the skills and expertise of their enslaved to produce a more lucrative and more easily grown crop in this particular area of southeastern North Carolina’s sandy loamy soil. The “goober,” a Gullah word for peanut, was not viewed as desirable for the dining table, let alone a staple of the gentry-class in the first half of the 19th century; however, Wilmington’s exports of peanuts, as well as North Carolina’s export of peanuts, was for some period of time one of the largest, if not the largest, in the colonies, and its export continued to be a thriving industry leading up to the Civil War, in which the peanut then became a staple among troops as an easy and cheap source of protein. The Foy and nearby Nixon plantations were instrumental in developing agricultural practices and emerging technologies to more efficiently harvest this cash crop precisely because of the farming practices and expertise of their enslaved.

Traditionally, basket-making and weaving were the tasks assigned of the enslaved women; whereas sweetgrass as mentioned earlier is the most common material used in coastal South Carolina to make baskets, enslaved women were resourceful and used materials most readily available, and in coast North Carolina, of course, the Long Leaf Pine needle was the most common material used to make baskets. We have a few examples of pine needle baskets in the Basket Gallery.

Food pathways are one of the more easily reflected cultural influences of the enslaved people at Poplar Grove and such pathways descended down through several generations of enslaved Foys who later remained as tenant farmers working and living here and on the nearby Nixon and Davis former plantations.

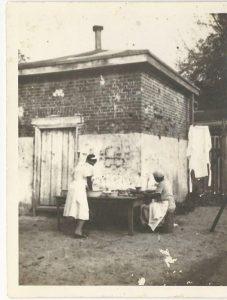

Gullah culture at Poplar Grove is also reflected in the production of swine, which was the main protein raised at Poplar Grove and an important dietary and income source. The hogs were set loose on the peanut fields after harvesting in the fall to fatten them up (see attached article of Carrie Simmons Ballard 1983) before slaughter in December and January. The meat was smoked in the smoke house that still has the stucco remnants of tabby, a cement mixture of oysters shells, lime, water, and sand in roughly equal parts, again introduced to the colonies by the Spaniards and 17th century slaves.

Like sweetgrass baskets, or more locally the Long Leaf Pine needle baskets, tabby is most often associated with buildings, garden walls, and the floors of slave dwellings of Georgia and South Carolina, but its remnants are on the floors and exterior walls of the smokehouse here at Poplar Grove, and along the main pathway from the manor house to the former peanut fields as well as along the original carriage pathway in front of the manor house, and further back behind the “big house” around the large oaks where the cabins of the enslaved once stood.

The complicated and intimate working relationship between the Foy family and the African American tenant families who remained at Poplar Grove also shared similar dishes through successive generations, and were all raised on Hoppin’ John, biscuits and molasses, sweet potatoes, BBQ and smoked pork, okra and tomatoes, and – because of the proximity of the Atlantic coast – shrimp, fish, and oysters (of course) were daily incorporated into their dishes.

No one captures southeastern North Carolina and the Gullah Geechee community as remarkably as local artist, Ivey Hayes. Poplar Grove’s founder, Jan M. Lewis, was a huge supporter of Ivey Hayes, and we are delighted to have UNCW art history intern, Anna Van De Carr, create an exhibit of some of Jan M. Lewis’ collection of Hayes’ prints this spring. View Van De Carr’s write-up of Ivey Hayes’ painting, Picking Peanuts, here.

It is through extensive examination of the archives here at Poplar Grove, along with new information that continues to emerge, that a more comprehensive history of Gullah culture emerges. However, a more thorough examination is required by scholars in the field to fully understand the resources here on site and within the Scotts Hill community – Caroline C. Lewis, Executive Director, Poplar Grove Foundation, Inc.

This page, and corresponding links, are continually being updated as research continues…

Sources

Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission (GGCHCC). Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Management Plan. Prepared and published by the National Park Service, Denver Service Center, 2012.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York, New York, 2000-2014.

National Park Service (NPS). Low Country Gullah Culture Special Resource Study and Final Environmental Impact Statement. Atlanta, GA: NPS Southeast Regional Office, 2005.